Marisa Merz

Marisa Merz was born in Turin, Italy in 1926. As a visual artist she was self-taught. In 1960 she married Mario Merz (1925-2003), who became known as one of the main representatives of Arte povera through the construction of igloos from a wide variety of materials and his use of the Fibonacci sequence. In 1975 Marisa Merz received her first solo exhibition at Galleria L'Attico in Rome, Italy. Her artistic breakthrough came in the 1990s with exhibitions including 1994 at the Musée National d'Art Moderne, (Centre Pompidou), Paris, France and the Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Winterthur, Switzerland. In 2018, the Museum der Moderne Salzburg, took over the highly acclaimed retrospective "Il Cielo È Grande Spazio / The Sky is a Wide Space," organized in the United States by the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in cooperation with the Fundação de Serralves - Museu de Arte Contemporânea in Porto, Portugal, for which a detailed catalog was published. Merz participated in numerous group exhibitions, including documenta 7 in 1982 and documenta IX in 1992 ,as well as the 43rd and 49th Biennale di Venezia (1988 and 2001). On the occasion of the 55th Biennale di Venezia (2013) she was awarded the Golden Lion for her life's work. Marisa Merz passed away in 2019 in Turin.

Marisa Merz’s artistic work was continually developing, initially in private and in parallel to the arte povera movement, which was dominated by men. Much later, Merz succeeded in emerging from the shadow of her famous husband and gaining recognition as an artist in her own right.

The term arte povera was coined in 1967 by the art historian, critic, and internationally renowned curator Germano Celant (1940–2020). The term stood for a movement in art that formed in the late 1960s in northern Italy, which Celant wished to distinguish from American minimalism as an independent and valuable European phenomenon. This “poor art” is notable for its use of everyday and banal materials—“poor” substances that had hitherto not been seen as relevant to art. These included earth, plants, stones, glass, and others. Marisa Merz and the Hamburg-born Eva Hesse (1936–1970), who had fled with her Jewish family to New York in 1939, are the only two female representatives of arte povera. With her revolutionary spatial and sculptural use of everyday and mainly soft materials, like textiles, strings, felt, resin, latex, rubber, polyester, and glass fiber, Eva Hesse was a kind of link between European arte povera and American minimalism, and her work can be seen to belong to both movements. The focus was on overcoming conventional understandings of material and unleashing the creative potential and surprising intensive poetry of the simplest things. In Europe these were mainly natural, organic, and vegetable materials that had a rich potential for metaphor and great associative power. In the USA by contrast, artists used prefabricated industrial products like metal and stone tiles and steel, reducing them analytically to basic geometrical structures, forms, and monochrome surfaces. The allegedly simple objects of arte povera proved to be rich in content and full of wide-ranging references and allusions. Frank Stella, a protagonist of minimal art, was much more pragmatic: “What you see is what you see.” Minimalist artists rejected story-telling. Their works were intended to have the objective character of industrial products and to represent nothing other than what they were. Both arte povera and minimalism contributed to a far-reaching and revolutionary erosion of hitherto dominant values in art.

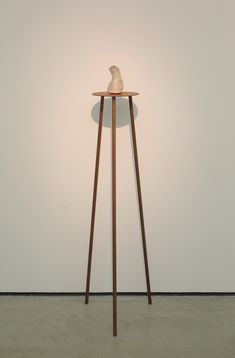

Marisa Merz worked mainly as a sculptor and installation artist. Her works addressed the theme of the fragment. Using materials like wax, clay, wood, hemp, canvas, paper, aluminum, and the copper wire that was key to her work and that she weaved with “typically feminine” skill, she developed her own personal formal idioms. One of her first works was Living Sculpture, made in the mid-1960s, a large sculptural creation made of flexible aluminum tubes that she hung from the kitchen ceiling in her Turin apartment. Over the years, this mobile and swinging metal structure, a strange hybrid of the organic and technical, was erected at various different locations and in various forms—made possible by the flexible tubes that could be packed up and rolled apart again like a fan. In the 1970s, the artist began to combine various single works to form large multi-part installations. In the 1980s and 1990s, she produced a series of expressive sculptures, the Testi (Heads). These are small ambivalent and ultimately unfathomable amorphous forms made of unfired clay, paraffin, lead, and pigment. As a conscious artistic strategy, Marisa Merz often did not date her works. By concealing the time of their production, she emphasized the open nature of these works.

The Generali Foundation Collection holds an ensemble of three representative works by Marisa Merz—an atmospheric drawing in graphite and metallic paint, a typical head sculpture, and a folding screen made of two pairs of wooden frames that can be stood up anywhere and that are densely covered with horizontally laid copper wire. The screen was made for a solo exhibition devoted to the artist at the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1994. In this work, Merz refers back to her very first solo show in 1975, where she laid copper wire horizontally along the gallery walls, thereby inscribing herself very physically into a specific space. In 1975 she made the private public, while the later folding screen reversed this principle and offered protection for the private sphere from the public gaze. The symbol of the shield and the energetic conductivity of copper, which can be read as a social metaphor, also play a role here. (Doris Leutgeb)